Maggie and the Freudian Slipper. Part Three: Conclusions

Now…first of all my sincere apologies for keeping you all in suspense about my search for Emilie. I had some rising out of the ashes to do, and one can't rise out of the ashes without turning into some first (which was the more time-consuming part of the process really). But I’m back and ready to kick some ass on the old typewriter again, so here's the conclusion to my search for the enigmatic Emilie.

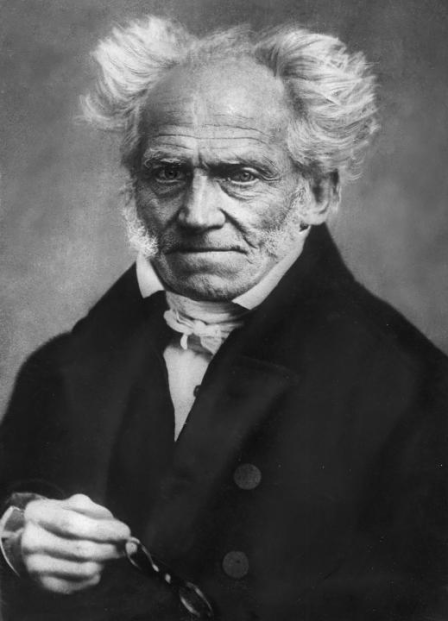

So, it’s 1842, the heyday of cultural and institutional misogyny. It was around this time that the notoriously grumpy philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer wrote that women have only one asset: their beauty. And this beauty is only there to lure men into taking care of them. Hence, as soon as the marriage is sealed the beauty will fade as in Schopenhauer’s view it then loses its natural function of cuckolding men. “The only thing they can take serious is love, and everything that is connected to it, like toiletries and fancy dancing.” One sees here a perfect illustration of the odd mix of deprecation and mortal fear so typical for misogyny.

Our Emilie in essence agreed with the grumpy old man, but turned his argument around by making the case for women being the stronger sex, because with one right tickle or twinkle they could break a man’s will, just like that. So naturally, I wanted to know more about this ingenious author.

But none of the — usually very complete — academic encyclopaedias of German authors even acknowledge Emilie Alfken’s existence. Only a 24-part encyclopaedia of 19th century German authors mentions her briefly, and it can only confirm that a book written by her appeared in 1842. In addition, it was all quiet on the Western Front when taking a look at genealogical records. One Emilie Alfken was found, but she was born in 1855, so no match there. So what do you do when you hit a brick wall? Then there is only one way to go, the historians escape hatch: to have a look at the context. And things still got rather interesting.

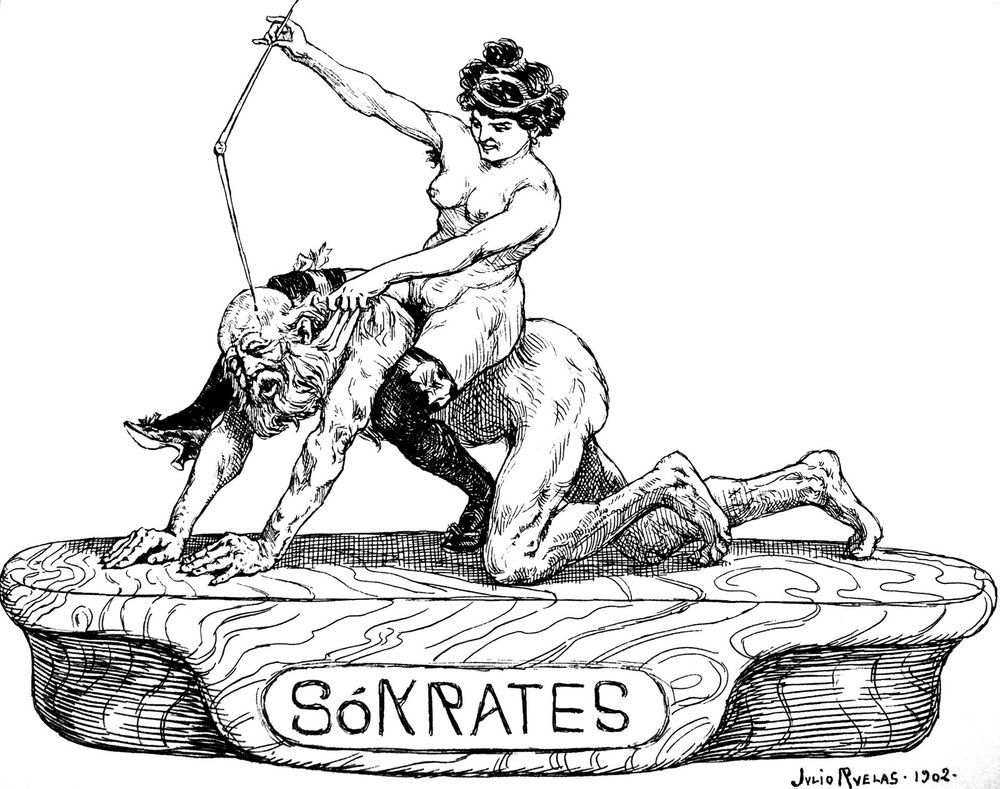

In Germany between the revolutions of 1830 and 1848, women started to step out of their traditional gender roles and penetrated the traditionally male territory of the belles-lettres. They started to “swing the pen instead of the needle.” Authors like Fanny Lewald and Louise Aston thematised and challenged the traditional gender roles in their writings. Making the sordid philosopher Johann Gottlieb Fichte cry out that women should keep writing what they are good at: guides for raising children and moral guides for fellow women. No way should they try themselves at things like novels, that would be anything but useful. Seemingly, the fear was after swinging their pen, women might also start swinging their slippers.

The Rubicon of male rule

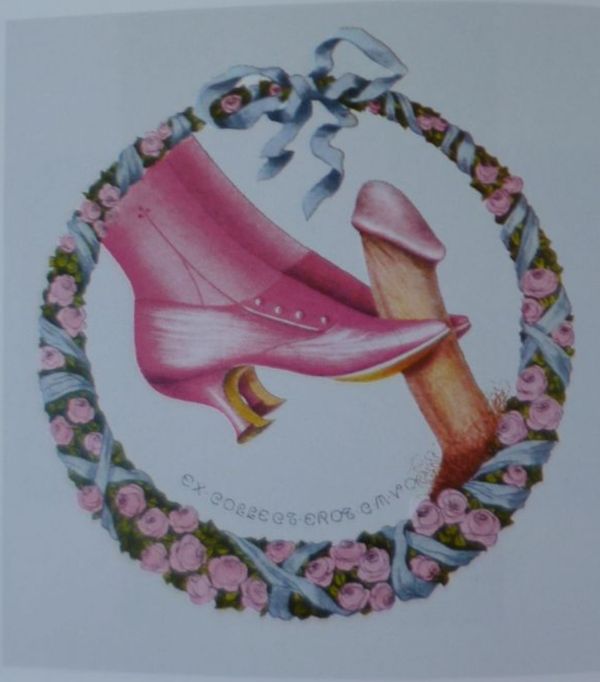

In 1832, an article titled “Slipper speech of an author and satirist on the day of his marriage” appeared in the newspaper Der Deutsche Horizont. It stated that “The slipper is the Rubicon of male rule.” The piece was reprinted in several other newspapers that year.

In 1836, the tenth volume of an anthology of the works of the poet Jean Paul Richter appeared that contained a short observation called the “Wife’s-Slipper-Reign”:

We poor drones and worker bees fly after and serve the Queen bees — how little do we resemble the Swedish, to whom King Charles the Twelfth promised to rule over them with his boot — when a slipper is enough to rule over us.

And these are only two examples of a flood of poems, stories,and jokes overly concerning themselves with the threat of the rule of the slipper. The historian James M. Brophy concluded in 2009 that the “Slipper Pamphlets” were part of a wider range of satirical pamphlets, often appearing around the traditional Mardi-Gras period, and were meant to criticize the passive obedience and culture of servitude in Germany. They didn't even need a boot to subdue them, a mere satin slipper was enough to get them on their knees. Brophy's statement could be valid, considering the agitative language that usually accompanies revolutionary moods. In that context, it could be that the author Emilie Alfken never existed for real. And that would explain why there is no further trace of her except for the ominous pamphlet. It could have been a nom de plume of an unknown satirist, wishing to make fun of the political culture in Germany of the days. And as politics was a male activity back then, who will you mock and who is the mocker? It could very well be that Emilie Alfken in the end was a man. The hints of academic language in the pamphlet, citing examples from scripture and classical history and mythology, could point to that as well. As despite all early feminist efforts it would take up unto 1900 before the first woman was admitted to a German university. But on the other hand, a girl could have picked things up sneaking into her father's library,

Female authors being forgotten by all and everyone to leave only their book as a trace in history are not unheard of, neither are savants. I’ve got one or two similar lingering cases, Nancy McKay Gordon, author of the 1902 title “The Majesty of Sex” is one of them. A woman of whom nothing seems to be known, not even by the omnipotent google, all seems to have forgotten about her except for what she wrote. And if there is anything like a soothing conclusion to this blog, before I put Emilie Alfken in my cold case cabinet, it is that whoever he or she was, the book still manages to stir the occasional imagination. Who knows? Maybe someone will be searching for me in two hundred years or so.